Home

Home  blog post by Donnie Welch

blog post by Donnie Welch

My #bookreview of the Foundation Trilogy through a #clifi lense!

Warning: This review contains ''spoilers'' (scare quotes for emphasis)

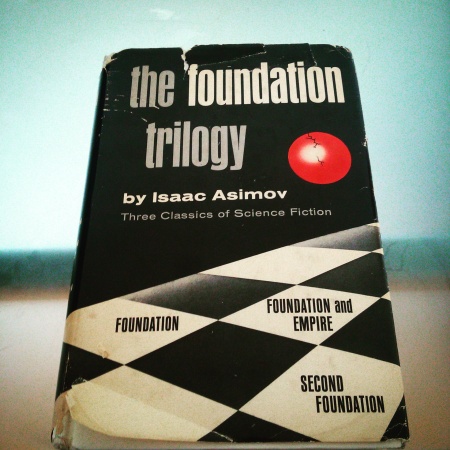

Issac Asimov is one of the masters of the ''skiffy'' genre and none of his works are quite as renowned as The Foundation Trilogy: Foundation, Foundation and Empire, Second Foundation. While each of these texts are worthy of individual reviews, I read them in a single collection and would like to review them in that form.

I’m reviewing them on The Frontier because I’d like to review them in the context of an emerging new literary genre, namely, Climate Fiction or Cli-fi.

'' Do you cli-fi?''

To quote a recent article in The Atlantic by JK Ullrich, ''Cli-Fi'' is “A new literary genre that focuses on the consequences of environmental issues…[and] the Earth’s sustainability.”

While I certainly don’t think Asimov’s intent with the Foundation series was to pen an environmental manifesto set in space, there are aspects in all three of the books that invite an environmental critique. Right from the onset, the reader is presented with a decaying galactic empire, and at the center of this dying empire is a capital world that’s so urbanized it can’t sustain itself:

When the First Foundation is confronted with their first crisis, a threat of war from a neighboring planet, the character Salvor Hardin, mayor of the First Foundation, remains calm and relatively unconcerned because

In Foundation and Empire when the protagonists are about to revisit the world of Trantor after the empire’s fall Asimov details a world in the process of reclaiming it’s landscape from urbanization:

While the Foundation Trilogy is remembered as a masterpiece of skiffy I contend that it also stands as an early example, or at the very least exhibits traits of, cli-fi. Asimov himself was concerned with environmental issues, especially nuclear energy and overpopulation, going so far as to co-author an environmental manifesto entitled ''Our Angry Earth'' so it doesn’t seem unreasonable for him to have subtly fit overarching environmental themes into his fictional work.

Issac Asimov is one of the masters of the ''skiffy'' genre and none of his works are quite as renowned as The Foundation Trilogy: Foundation, Foundation and Empire, Second Foundation. While each of these texts are worthy of individual reviews, I read them in a single collection and would like to review them in that form.

I’m reviewing them on The Frontier because I’d like to review them in the context of an emerging new literary genre, namely, Climate Fiction or Cli-fi.

'' Do you cli-fi?''

To quote a recent article in The Atlantic by JK Ullrich, ''Cli-Fi'' is “A new literary genre that focuses on the consequences of environmental issues…[and] the Earth’s sustainability.”

While I certainly don’t think Asimov’s intent with the Foundation series was to pen an environmental manifesto set in space, there are aspects in all three of the books that invite an environmental critique. Right from the onset, the reader is presented with a decaying galactic empire, and at the center of this dying empire is a capital world that’s so urbanized it can’t sustain itself:

“Daily, fleets of ships in the tens of thousands brought the produce of of twenty agricultural worlds to the dinner tables of Trantor… It’s dependence upon the outer worlds for food, and indeed, for all necessities of life, made Trantor increasingly vulnerable to conquest by siege.” Foundation page 8This kind of urbanization would have been similar to what Asimov was witnessing in the 1950s when these books were first published. In America people were beginning to migrate to cities, such as Asimov’s home of NYC, to find work, leaving fewer people in the rural parts of the country, and therefore less agricultural development. Yet, inversely, these growing cities needed all the resources they could get from the shrinking countryside in order to feed and support their burgeoning populations, creating an inequity that the fictional world of Trantor plays out on a grand scale.

When the First Foundation is confronted with their first crisis, a threat of war from a neighboring planet, the character Salvor Hardin, mayor of the First Foundation, remains calm and relatively unconcerned because

“‘…the rest of of the Periphery no longer has atomic power either. Certainly Smyrno hasn’t, or Anacreon wouldn’t have won most of the battles in their recent war.’… He threw his cigar away and looked up at the outstretched Galaxy. ‘Back to oil and coal are they?’ he murmured.” Foundation page 50The superiority of alternative energy forms, Atomic in the First Foundation’s case, isn’t pedantically described, rather Asimov quite brilliantly interweaves it into his narrative. The more adept society, especially in a universe with space travel, is obviously that which no longer has to rely on the dirty energy of oil and coal. Asimov was alive for the very beginnings of Nuclear energy, and the consequent disasters such as Three Mile Island, but this image of the future might hold more truth for our contemporary society where coal companies have begun going bankrupt and we’re forced with the need to retool and redesign our energy use.

In Foundation and Empire when the protagonists are about to revisit the world of Trantor after the empire’s fall Asimov details a world in the process of reclaiming it’s landscape from urbanization:

“Surrounded by the mechanical perfections of human efforts, encircled by the industrial marvels of mankind freed of the tyranny of the environment—they returned to the land. In huge traffic clearings, wheat and corn grew. In the shadow of the towers, sheep grazed.” Foundation and Empire page 183Despite this seemingly utopic, pastoral, image, Asimov doesn’t romanticize the state of agriculture, merely gives his reader a portrayal of what a new beginning after generations of urban sprawl might look like. In fact, in Second Foundation Asimov dispels any idealism of returning to the Earth or old-world customs by creating the feudal world of Rossem in which peasants are controlled by a council of Elders, who are controlled by a feudal lord, who are controlled imperially by a militant world and while the people live a simple life, i contrast with the technology and ambitions of the other worlds in the trilogy, they are impoverished and severely oppressed:

“‘It is not good to think of for we are humble men who are poor farmers and not concerned with matters of politics'” Second Foundation page 43When the reader returns to the world of Trantor in Second Foundation, the final book of the trilogy, Asimov describes once more the process of recovery, this time more refined and organized as professional agriculture conglomerates are selling their goods across the galaxy.

“The soil was uncovered once more and the planet returned to it’s beginnings. In the spreading areas of primitive agriculture, it forgot it’s intricate and colossal past” Second Foundation page 181However, that isn’t all Trantor contains. In a clever turn, it is this emerging agricultural world that holds the powerful Second Foundation, a group that contains the mental scientists and therefore the prowess to eventually control the galaxy and establish the ruling class of Hari Seldon’s second empire. Asimov’s decision to place the future strength of the entire galaxy in the hands of a pastoral world seems more than a plot point.

While the Foundation Trilogy is remembered as a masterpiece of skiffy I contend that it also stands as an early example, or at the very least exhibits traits of, cli-fi. Asimov himself was concerned with environmental issues, especially nuclear energy and overpopulation, going so far as to co-author an environmental manifesto entitled ''Our Angry Earth'' so it doesn’t seem unreasonable for him to have subtly fit overarching environmental themes into his fictional work.

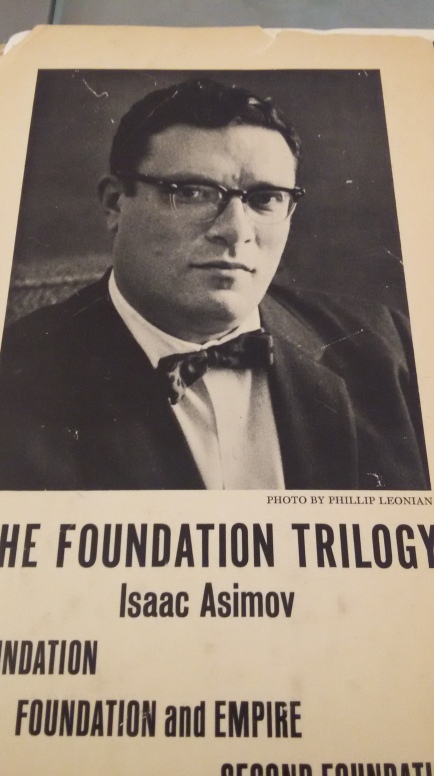

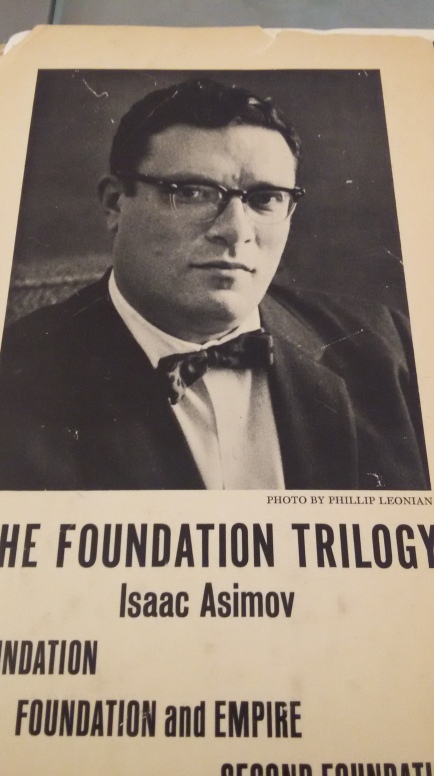

This guy wants YOU to consider environmental ethics in a universal context.

No comments:

Post a Comment